Analizar las redes sociales de los revolucionarios de Boston con el lenguaje de Wolfram

Swede White, Especialista en Medios y ComunicacionesWolfram Blog

A medida que se acerca el 4 de julio, muchos en América celebrarán 241 años desde que los fundadores de los Estados Unidos de América firmaron la Declaración de Independencia, su propia y revolucionaria empresa revolucionaria. Antes de la independencia, los colonos celebraban el nacimiento del rey. Sin embargo, después de la Guerra Revolucionaria estalló en abril de 1775, algunos colonos comenzaron a celebrar funerales simulados del Rey Jorge III. Además, las hogueras, los cañonazos festivos y el fuego de mosquetes y los desfiles eran comunes, junto con las lecturas públicas de la Declaración de Independencia. También había ron.

Hoy, a menudo celebramos con barbacoa, fuegos artificiales y una serie de otras festividades. Como aspirante a nerd de datos y sociólogo, pensé que usaría Wolfram Language para explorar la Declaración de Independencia usando un procesamiento básico del lenguaje natural.

Usando metadatos, también exploraré una red política de colonos con especial atención prestada a Paul Revere, utilizando las funciones integradas de Wolfram Language y la ciencia de redes para descubrir algunas verdades ocultas sobre el Boston colonial y sus actores clave antes de la firma de la Declaración de la independencia.

La Declaración de Independencia y el repositorio de datos de Wolfram

Wolfram Data Repository se anunció recientemente y contiene una creciente colección de recursos interesantes para resultados fácilmente computables.Da la casualidad que el repositorio de datos de Wolfram incluye el texto completo de la Declaración de Independencia. Exploremos el documento con WordCloud, tomándolo primero del Repositorio de Datos.

Interesante, pero esto no es muy patriótico por tema, así que use ColorFunction y luego use DeleteStopwords para eliminar a los firmantes del documento.

Como podemos ver, Wolfram Language ha eliminado los nombres de los firmantes y ampliado las palabras en función de su frecuencia en la Declaración de Independencia. Lo que destaca es que las palabras "leyes" y "personas" aparecen con mayor frecuencia. Esto no es terriblemente sorprendente, pero echemos un vistazo al uso histórico de esas palabras usando la funcionalidad incorporada de WordFrequencyData y DateListPlot para la visualización. Siguiendo con un tema patriótico, usemos también PlotStyle para hacer que la trama sea roja y azul.

Lo que es increíblemente interesante es que podemos ver un pico de uso alrededor de 1776 en ambas palabras. La divergencia entre el uso de las dos palabras a lo largo del tiempo también me parece interesante.

Una red social de Boston colonial

Según los textos históricos, el Boston colonial era un lugar fascinante a fines del siglo XVIII. La monografía de David Hackett Fischer, El viaje de Paul Revere, presenta una imagen completa de las facciones políticas que estaban impulsando el movimiento revolucionario. De particular interés son las logias masónicas y grupos de caucus que fueron políticamente activos y centrales para la Guerra Revolucionaria.Aquellos de nosotros que crecimos en los Estados Unidos probablemente recordaremos a Paul Revere de nuestras primeras clases de historia en Estados Unidos. Él famoso cabalgó un caballo a través de lo que ahora es la gran área de Boston advirtiendo a la milicia colonial de las tropas británicas entrantes, conocido como su "paseo de medianoche", notablemente capturado en un poema de Henry Wadsworth Longfellow en 1860.

Hasta la exploración de Fischer de las asociaciones políticas y membresías de las bancadas de Paul Revere, los historiadores argumentaron que el movimiento rebelde colonial estaba controlado por élites políticas de alto rango lideradas por Samuel Adams, y muchos concluyeron que Revere era simplemente un mensajero. Eso era, pero a través de ese mensaje y otras actividades, fue clave para unir grupos políticos que de otro modo podrían no haberse comunicado, como mostraré a través del análisis de redes.

Da la casualidad que esta vez el año pasado estuve en la Wolfram Summer School, actualmente en curso en Bentley University. Uno de los aspectos más destacados de mi tiempo fue una conferencia sobre análisis de redes sociales, dirigida por Charlie Brummitt, que utilizó metadatos para analizar rebeldes coloniales en Boston.

El sociólogo de la Universidad de Duke, Kieran Healy, tiene una fantástica publicación en el blog que explora el tema "Uso de metadatos para encontrar a Paul Revere" de la cual se deriva la conferencia. Voy a recrear algunos de sus análisis con Wolfram Language y llevar las cosas un poco más allá con visualizaciones más avanzadas.

"Recuerda a las mujeres"

En primer lugar, sin embargo, como sociólogo, mis estudios e investigaciones a menudo se refieren a las desigualdades, el poder y los grupos marginados. Sería negligente si no hubiera pensado en la correspondencia de Abigail Adams con su esposo John Adams el 31 de marzo de 1776, en la que ella le instruyó a "recordar a las damas" en las actas del Congreso Continental. Hice una WordCloud de la carta aquí.

Los datos que estamos utilizando se refieren exclusivamente a hombres y datos de membresía de organizaciones sociales y políticas exclusivamente masculinas. Vale la pena señalar que durante el período Revolucionario, y durante bastante tiempo después, a las mujeres se les prohibió legalmente participar en la mayoría de los asuntos políticos. Las mujeres podían votar en algunos estados, pero entre 1777 y 1787, esos derechos fueron despojados en todos los estados excepto Nueva Jersey. No fue hasta el 18 de agosto de 1920 cuando se aprobó la 19ª Enmienda, lo que garantizó el derecho de las mujeres a votar de manera inequívoca.

Con ese fin, según el derecho consuetudinario inglés, las mujeres eran tratadas como fem encubiertas, lo que significaba que los derechos de las mujeres casadas eran absorbidos por sus maridos. No solo no se les permitía votar, las leyes de cobertura dictaban que el esposo y la esposa eran una sola persona, ya que el primero tenía la autoridad exclusiva para tomar decisiones políticas, así como la capacidad de comprar y vender propiedades y ganar salarios.

Después de la Revolución Americana, Estados Unidos estuvo libre de la tiranía del Rey Jorge III; sin embargo, las mujeres seguían estando sumisas a los hombres legal y culturalmente. Por ejemplo, Hannah Griffitts, una poeta conocida por su trabajo sobre las Hijas de la Libertad, "The Female Patriots", expresada en un diario de 1785, sentimientos de entrada comunes entre muchas mujeres coloniales:

The glorious fourth—again appearsHay pocas dudas de que sin el trabajo doméstico y emocional de las mujeres, a menudo invisible en la historia, estos hombres, los llamados Padres Fundadores, habrían sido menos exitosos y expeditos en el logro de sus objetivos de independencia de Gran Bretaña. Así que hoy, recordamos a las mujeres, los marginados y los privados de derechos.

A Day of Days—and year of years,

The sum of sad disasters,

Where all the mighty gains we see

With all their Boasted liberty,

Is only Change of Masters.

Grupos políticos del Boston colonial: obtención de datos y análisis exploratorio

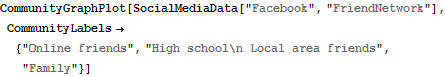

Convenientemente, cargué una matriz de asociación limpia de miembros de grupos políticos en Boston colonial como ResourceObject para el Repositorio de Datos. Importaremos con ResourceData para proporcionarnos un buen marco de datos con el que trabajar.Podemos ver que tenemos 254 colonos en nuestro conjunto de datos. Echemos un vistazo a los grupos coloniales rebeldes de los que Samuel Adams era miembro, ya que es conocido en la actualidad por ser un ingrediente clave en las celebraciones del 4 de julio, la cerveza.

Nuestros valores True/False indican membresía en una de las siete organizaciones políticas: St. Andrews Lodge, Loyal Nine, North Caucus, Long Room Club, Tea Party, Boston Committee of Correspondence y London Enemies.

Podemos ver que Adams fue miembro de cuatro de estos. Echemos un vistazo a las membresías de Revere.

Como podemos ver, Revere fue un poco más involucrado, ya que es miembro de cinco grupos. Podemos graficar fácilmente su membresía en estas organizaciones políticas. Para aquellos de ustedes que no están familiarizados con el funcionamiento de una red, los nodos representan a los agentes y las líneas entre ellos representan algún tipo de conexión, interacción o asociación.

Hay siete organizaciones en total, así que veamos cómo están conectadas destacando las organizaciones políticas como nodos rojos, con individuos conectados a cada nodo.

Podemos ver que Tea Party y St. Andrews Lodge tienen muchos más miembros que Loyal Nine y otros, que ahora exploraremos más a fondo en el nivel micro.

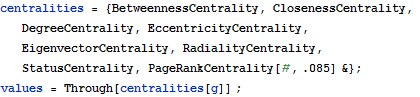

Red de personas en organizaciones políticas: cercanía y centralidad

Lo que hemos hecho hasta ahora es bastante macro y exploratorio. Analicemos detenidamente la conexión de cada individuo entre sí a través de la membresía compartida en estos diversos grupos. Esencialmente, estamos eliminando nuestros nodos de organización política y centrándonos en los colonos individuales. Utilizaremos Tooltip para ayudarnos a identificar a cada actor en la red.Ahora usamos un método de red social llamado BetweennessCentrality que mide la centralidad de un agente en una red. Es la fracción de las rutas más cortas entre pares de otros agentes que pasan a través de ese agente. Dado que el actor puede intermediar información entre los otros agentes, por ejemplo, esta medida se vuelve clave para determinar la importancia de un nodo particular en la red midiendo cómo se encuentra un nodo entre pares de actores sin nada que se encuentre entre un nodo y otros actores.

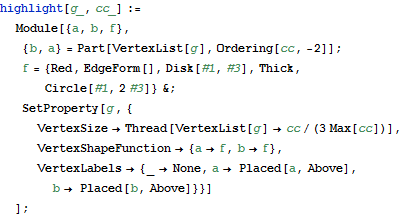

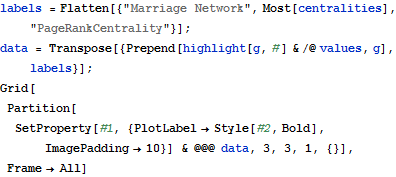

Primero crearemos una función que nos permitirá visualizar no solo BetweennessCentrality, sino también EigenvectorCentrality y ClosenessCentrality.

Comenzamos con un breve código para BetweennessCentrality que utiliza la función ColorData definida para mostrarnos qué actores tienen la mayor capacidad para transmitir recursos o información a través de la red, junto con la información sobre herramientas que se definió previamente.

Y he aquí, Paul Revere parece tener una puntuación de interinidad mucho más alta que cualquier otra persona en la red. Significativamente, John Adams está en el centro de nuestro gráfico radial, pero no parece tener mucho poder en la red. Tomemos los números.

Revere tiene casi el doble del puntaje del siguiente colono más alto, Thomas Urann. Lo que esto indica es la importancia esencial de Revere en la red como intermediario de información. Como él es miembro de cinco de los siete grupos, esto no es terriblemente sorprendente, pero de lo contrario hubiera pasado desapercibido sin este tipo de investigación.

La cercanía La centralidad varía de la intermedia en que nos preocupamos por la longitud de la ruta a otros actores. Estos agentes que pueden llegar a un gran número de otros actores a través de trayectos cortos pueden diseminar información o incluso ejercer el poder de manera más eficiente que los agentes en la periferia de la red. Ejecutamos nuevamente nuestra función en la red y miremos a ClosenessCentrality para ver si Revere todavía se encuentra en la posición más alta.

Revere aparece clasificado como el más alto, pero no es tan dramático como su puntaje de intermediación y, de nuevo, John Adams tiene un puntaje bajo. Tomemos las medidas para un análisis posterior.

Como indica nuestra coloración del mapa de calor de los nodos, otros colonos no se quedan atrás de Revere, aunque sin duda es el mejor clasificado. Si bien hay otras personas importantes en la red, Revere es claramente el intermediario más eficiente de recursos, poder o información.

Una medida final que podemos examinar es EigenvectorCentrality,, que utiliza un algoritmo más avanzado y tiene en cuenta la centralidad de todos los nodos y la cercanía e incrustación de un actor individual entre los agentes altamente centrales.

Parece haber dos contendientes principales para la puntuación más alta del vector propio. Volvamos a calcular las medidas en una tabla para su examen.

Nathaniel Barber y Revere tienen puntajes casi idénticos; sin embargo, Revere todavía encabeza la lista. Tomemos ahora los cinco primeros puntajes de cercanía y creemos una red sin ellos para ver cómo podría cambiar la cohesión de la red.

.

Vemos un cambio bastante dramático en el gráfico de la izquierda con nuestros jugadores clave eliminados, lo que indica que aquellos con los cinco primeros puntajes de cercanía son bastante esenciales para unirse a estas siete organizaciones políticas juntas. Joseph Warren parece ser una de las pocas personas que puede actuar como un puente entre grupos dispares de conexiones. Básicamente, sería difícil que la información se distribuyera libremente a través de la red de la izquierda en oposición a la red de la derecha que incluye a Paul Revere.

Conclusión

Como hemos visto, podemos usar la ciencia de redes en la historia para descubrir o exponer ideas preconcebidas sobre la importancia de una figura en eventos históricos, según los metadatos de membresía grupal. Antes del análisis de Fischer, muchos pensaban que Revere era solo un mensajero, y no una figura importante. Sin embargo, lo que he podido mostrar es la importancia de Revere para unir grupos políticos dispares. Esto revela aún más que el movimiento Revolucionario fue pluralista en sus objetivos. En última instancia, la red estuvo unida por el desdén por la tiranía del rey Jorge III, las injustas acciones militares británicas y las políticas que llevaron a una sangrienta revuelta, no necesariamente una directiva descendente de las elites políticas.Más allá de la historia, la ciencia de la red y el procesamiento del lenguaje natural tienen muchas aplicaciones, como descubrir agentes de información, recursos y poder, es decir, capital social ocultos. Uno puede imaginar fácilmente cómo esto podría ser útil para el marketing computacional o las relaciones públicas.

¿Cómo utilizará la ciencia de la red para descubrir ideas ocultas que de otra manera revolucionarán e interrumpirán su trabajo o sus intereses?