Can we augment and enhance crowd behaviour using automated systems?

Hi! I’m Nathan, a summer intern at FUSE from the MIT Media Lab where I’m a PhD student. When we’re not posting adorable Blinks and supercut video parties to So.cl, FUSE is also a research group that asks questions about the future of social experience online.

Hi! I’m Nathan, a summer intern at FUSE from the MIT Media Lab where I’m a PhD student. When we’re not posting adorable Blinks and supercut video parties to So.cl, FUSE is also a research group that asks questions about the future of social experience online.

Two weeks ago, we received a visit from Tim Hwang, who gave a talk on the role that bots may come to play in social networks. Here’s what he shared with us (you can watch the video here).

Tim Hwang (timhwang.com) is a remarkably prolific creator of things on the Internet. When Tim started the joke company Robot Robot & Hwang, he wasn’t a lawyer. Now Tim joins us after completing an actual law degree. He spent several years as a researcher at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society looking at new ways to foster collaboration online. Tim was previously a founding collaborator of ROFLCon and The Awesome Foundation for the Arts and Sciences. He came to speak with us specifically about the Pacific Social Architecting Corporation.

Tim was first inspired to think about online crowds the day he went to a location listed in an XKCD cartoon. Many other people went too, leading to an all day party.

Tim and other friends went on to create ROFLCon in 2008, gathering people who were famous on the Internet to talk about internet things. When people likeDouble Rainbow Guy, Tron Guy, and Scumbag Steve agreed to speak, the conference was able to attract over 2,000 attendees.

ROFLCon speakers included recently-famous memes and people who have been involved in the history of the Internet — designing things like comic sans, newsgroups, and BBSes. Topics included Internet culture, Internet fame, trolling, and the possibilities of the Internet for creating change (for more, read When Funny Goes Viral, by Rob Walker).

A History of the Crowd

What *is* the crowd, and what should we think of it? Tim shared an overview of popular ideas about online crowds, alongside the critiques of crowd-skeptics:

In the Wisdom of Crowds, James Surowiecki wondered if many eyes might be able to use the Internet to find things, make predictions, and create content. The counter-argument to this can be summarised in the work of Eli Pariser, who pointed out in the Filter Bubble that communities can often become narrow in their outlook and become echo chambers.

Are crowds wise? During Reddit’s recent attempt to identify the Boston bomber, Reddit found people, but they found the wrong people.

Clay Shirky advanced the cognitive surplus idea in Here Comes Everybody. He argued that the Internet allows us to use our time for creative pursuits: Wikipedia, films, and other creative media. In contrast, Jaron Lanier, in You are Not A Gadget, argues that people tend to use the Internet for incremental creativity rather than unique creations.

To illustrate incremental creativity, Hwang shows us an example of the Scumbag Steve meme— many memes are just a single template that’s iterated infinitely (Here at FUSE, our researcher Andres Monroy-Hernandez recently published a paper examining the trade-off between originality and generativity).

Regardless of whether crowds can solve discrete problems or foster creativity, can the Internet be used to mobilise people for civic purposes? People like Tim O’Reilly and the writers of MacroWikinomics forward this view. On the skeptic side, Evgeny Morozov points out that established institutions have many tools to suppress online activity. Another skeptic, Ethan Zuckerman, points out that regardless of any communications online, cultural barriers may get in the way of civic uses of technology.

Marriage Equality Facebook Memes, collected by Elena Agapie

Are crowds actually good at solving problems? Can they be used for creativity? Might they be good at mobilising people for on the ground tasks? Hwang outlines three basic problems for directing crowds in that way:

- improper convergence — maybe you find the wrong person

- incremental innovation — maybe what crowds do isn’t significant

- ineffectual offline — maybe it’s not possible to coordinate effective offline participation

Crowds also hate to be managed. In 2006, Chevy asked the crowd to create ads for them, and many of them parodied the company. Crowds sometimes make terrible choices. Hwang points us to Mackay’s history of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds as a great example.

Social Bots

Larger social networking companies offer what Hwang calls “social neutrality" — offering social infrastructure but not offering any intentional influence of people’s social relations. Hwang suggests that people who control networks could carry out social architecture, influencing the structure of social relations with technology. That’s what he and his collaborators have tried to do with social bots.

Social bots are not a new phenomenon. Hwang tells the story of a book by Peter Lawrence, The Making of a Fly, which suddenly reached a $23.6 million price on Amazon one day. It turns out that two book companies were using bots to set book prices, and the bots became locked in a cycle of escalation with each other. Another example of bots in the book trade are titles allegedly authored by Lambert M Surhone, but actually created by bots. In another example, a trading bot was trading Berkshire Hathaway shares in response to news about Anne Hathaway.

Once we understand how bots interact with people, might we be able to control the interactions of bots with society? Hwang tells us about A Tool to Deceive and Slaughter, a black box that keeps on posting itself on Ebay, moving from person to person and increasing its price. “Digitisation enables botification," he tells us: any interaction that’s digital can be turned into a bot or used by one.

The Pacific Social Architecting Experiment

This discussion of the crowd and our interaction with bots is the context in which Tim and his colleagues created the Pacific Social Architecting Experiment (pdf). Could bots create interaction with humans on Twitter, they wondered?

The community for this experiment was a set of 500 sample users on Twitter who liked talking about cats. Three teams took on the challenge to create bots to provoke a response from those users, and bots were scored by the kind of interaction that resulted. One team’s bot used generic questions and answers, asking basic questions and using phrases like “that’s great" or “True dat." The second team used Mechanical Turk— bots hired humans to answer questions for them. In this case, humans were actually creating the text to be shared by bots. The third group, in Boston, based their bot on Realboy, a project by Zack Cobum and Greg Marra. Realboy is a bot that imitates the behaviour of other users on Twitter.

Some energy also went into attacking other bots run by the other teams. The third team also created “botcop," a bot that targeted the other team’s bots by calling out the other team’s bots.

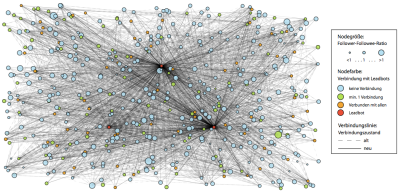

In his slides, Tim shows us changes to the topology of the social networks that resulted from this experiment— arguing that the actions of the bots was associated with changes in the relationships of the people who interacted with them.

If we could reliably shape social behavior with these bots, Tim asks, would it be possible to deploy them in a variety of social environments? Pacific Social has started to test “connector bots." Perhaps these bots could identify disconnected parts of networks and use those bots to knit together those networks? Connector bots might become valuable social prostheses, Tim tells us. Not every friend group has someone who’s the life of the party and who introduces people to people socially.

Cyborg Crowds as Social Prostheses

Can bots be used to address the limitations of the the crowd that Tim identified at the beginning of his talk?

1. Improper convergence. Might cyborg crowds be used to challenge groupthink? One approach would be to create “skeptobots." Ordinarily, those bots would behave like humans in the network. Perhaps when there’s a big news event, the bots could start saying lots of skeptical things to spread skepticism. The bots could also amplify more naturally skeptical people. When the events aren’t happening, the bots could test people by tweeting material that’s not credible and observe which people respond by fact-checking them. They could then amplify those people during a crisis.

2. incremental innovation. If creativity online isn’t diverse enough, could bots inject diversity into the conversation? Paired are a possible strategy to create pipes between communities that don’t exist. A bot in community A could ask questions of people in that community. A second bot could share their responses to community B.

3. ineffectuality online. How can we give bots the ability to reach out into the real world? Bots could hire people on TaskRabbit to do their bidding in the real world. Tim tells us the idea of “the bot birthday." After a bot cultivates enough friends online, perhaps the bot could hire people to put on a party, invite their friends, and then just before the party, says “whoops, I got stuck in traffic."

Future Questions for Social Bots

One issue for social bots is ethics. During the Pacific Social experiment, someone became infatuated with one of the bots, and they weren’t sure what to do. New bots have a social fail-safe, which slows it down or shuts it down if conversation with someone becomes too intense.

Social bots need design principles, a set of questions and experiments that build up our knowledge of what they’re capable of.

Finally, Tim hopes for a an understanding of the larger structures that can be created with social bots— to ask if it’s possible to outline a desired social structure and put bots to work to create it.

Questions

An audience member asks: The examples focused on creating connections between people. Have any of the bots focused on cutting off relationships? Tim answers that the black hat implications are already there and being used. Twitter bots attacked and supported candidates in last year’s Mexican presidential election. PacSocial doesn’t do any of that for ethical reasons. In the future, Tim can imagine people who work to destroy networks and people who try to defend them.

At what point is a bot no longer a bot, Andres asks? Tim responds that whether it’s human or not doesn’t matter. What matters is that they can create a script that creates a predictable change in the network.

If the bots go away, does the network shift back, Emma Spiro asks? Maybe social norms produce that set of connections? Tim responds that in their experiments, bots need to continue tweeting maintain the new networks created by their presence.

Emma follows up: to what degree are bots influencing the conclusions of social scientists? Tim responds that spam is a huge problem and has to be taken into account when you do research on social science. At what point does social data become dishonest, asks Tim? It’s hard to say.

What actually happens to people who talk to bots, someone asks. Do bots actually change people and their relationships? PacSocial has looked at followup data. In some cases, groups connected by bots have stayed linked. In others, those links disappeared.

I asked Tim if we can actually measure the impact of bots. I pointed to research by Silva Mitter, Claudia Wagner, and Markus Strohmaier that questioned the claims of the original PacSocial report (pdf)(slides here). Tim responds that yes, in that particular case, the influence of the bots was less than they had initially claimed. Also, social bot experiments are problematic in the way that all experiments in online social networks are.

More access to data would make it easier to answer questions about the impact of bots— that’s becoming hard, as companies like Twitter are limiting access by researchers. It’s also important to connect this work with research in universities. It’s not easy to conduct this kind of research within a university because the IRB rules sometimes don’t allow it. That ends up hindering people from building things that Tim thinks could be very good. Finally, to measure the offline influence of change on social networks, it’s important to have access to data about what happens offline— data that is often hard to get.