Este blog reúne material del curso de posgrado "Análisis de redes sociales" dictado en la Universidad Nacional del Sur (Argentina).

miércoles, 5 de septiembre de 2012

jueves, 23 de agosto de 2012

Ciencias social computacionales y redes sociales

Computational social science: Making the links

From e-mails to social networks, the digital traces left by life in the modern world are transforming social science.

Jon Kleinberg's early work was not for the mathematically faint of heart. His first publication1, in 1992, was a computer-science paper with contents as dense as its title: 'On dynamic Voronoi diagrams and the minimum Hausdorff distance for point sets under Euclidean motion in the plane'.

That was before the World-Wide Web exploded across the planet, driven by millions of individual users making independent decisions about who and what to link to. And it was before Kleinberg began to study the vast array of digital by-products generated by life in the modern world, from e-mails, mobile phone calls and credit-card purchases to Internet searches and social networks. Today, as a computer scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, Kleinberg uses these data to write papers such as 'How bad is forming your own opinion?'2 and 'You had me at hello: how phrasing affects memorability'3 — titles that would be at home in a social-science journal.

Related stories

“I realized that computer science is not just about technology,” he explains. “It is also a human topic.”

Kleinberg is not alone. The emerging field of computational social science is attracting mathematically inclined scientists in ever-increasing numbers. This, in turn, is spurring the creation of academic departments and prompting companies such as the social-network giant Facebook, based in Menlo Park, California, to establish research teams to understand the structure of their networks and how information spreads across them.

“It's been really transformative,” says Michael Macy, a social scientist at Cornell and one of 15 co-authors of a 2009 manifesto4 seeking to raise the profile of the new discipline. “We were limited before to surveys, which are retrospective, and lab experiments, which are almost always done on small numbers of college sophomores.” Now, he says, the digital data-streams promise a portrait of individual and group behaviour at unprecedented scales and levels of detail. They also offer plenty of challenges — notably privacy issues, and the problem that the data sets may not truly be reflective of the population at large.

Nonetheless, says Macy, “I liken the opportunities to the changes in physics brought about by the particle accelerator, and in neuroscience by functional magnetic resonance imaging”.

Social calls

An early example of large-scale digital data being used on a social-science issue was a study in 2002 by Kleinberg and David Liben-Nowell, a computer scientist at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota. They looked at a mechanism that social scientists believed helped drive the formation of personal relationships: people tend to become friends with the friends of their friends. Although well established, the idea had never been tested on networks of more than a few tens or hundreds of people.

Kleinberg and Liben-Nowell studied the relationships formed in scientific collaborations. They looked at the thousands of physicists who uploaded papers to the arXiv preprint server during 1994–96. By writing software to automatically extract names from the papers, the pair built up a digital network several orders of magnitude larger than any that had been examined before, with each link representing two researchers who had collaborated. By following how the network changed over time, the researchers identified several measures of closeness among the researchers that could be used to forecast future collaborations5.

As expected, the results showed that new collaborations tended to spring from researchers whose spheres of existing collaborators overlapped — the research analogue of 'friends of friends'. But the mathematical sophistication of the predictions has allowed them to be used on even larger networks. Kleinberg's former PhD student, Lars Backstrom, also worked on the connection-prediction problem — experience that he has put to good use now that he works at Facebook, where he designed the social network's current friend-recommendation system.

Another long-standing social-science idea affirmed by computational researchers is the importance of 'weak ties' — relationships with distant acquaintances who are encountered relatively rarely. In 1973, Mark Granovetter, a social scientist now at Stanford University in Stanford, California, argued that weak ties form bridges between social cliques and so are important to the spread of information and to economic mobility6. In the pre-digital era it was almost impossible to verify his ideas at scale. But in 2007, a team led by Jukka-Pekka Onnela, a network scientist now at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, used data on 4 million mobile-phone users to confirm that weak ties do indeed act as societal bridges7 (see 'The power of weak ties').

In 2010, a second group, which included Macy, showed that Granovetter was also right about the connection between economic mobility and weak ties. Using data from 65 million landlines and mobile phones in the United Kingdom, together with national census data, they revealed a powerful correlation between the diversity of individuals' relationships and economic development: the richer and more varied their connections, the richer their communities8 (see 'The economic link'). “We didn't imagine in the 1970s that we could work with data on this scale,” says Granovetter.

Infectious ideas

In some instances, big data have showed that long-standing ideas are wrong. This year, Kleinberg and his colleagues used data from the roughly 900 million users of Facebook to study contagion in social networks — a process that describes the spread of ideas such as fads, political opinions, new technologies and financial decisions. Almost all theories had assumed that the process mirrors viral contagion: the chance of a person adopting a new idea increases with the number of believers to which he or she is exposed.

Kleinberg's student Johan Ugander found that there is more to it than that: people's decision to join Facebook varies not with the total number of friends who are already using the site, but with the number of distinct social groups those friends occupy9. In other words, finding that Facebook is being used by people from, say, your work, your sports club and your close friends makes more of an impression than finding that friends from only one group use it. The conclusion — that the spread of ideas depends on the variety of people that hold them — could be important for marketing and public-health campaigns.

As computational social-science studies have proliferated, so have ideas about practical applications. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, computer scientist Alex Pentland's group uses smartphone apps and wearable recording devices to collect fine-grained data on subjects' daily movements and communications. By combining the data with surveys of emotional and physical health, the team has learned how to spot the emergence of health problems such as depression10. “We see groups that never call out,” says Pentland. “Being able to see isolation is really important when it comes to reaching people who need to be reached.” Ginger.io, a spin-off company in Cambridge, Massachusetts, led by Pentland's former student Anmol Madan, is now developing a smartphone app that notifies health-care providers when it spots a pattern in the data that may indicate a health problem.

Other companies are exploiting the more than 400 million messages that are sent every day on Twitter. Several research groups have developed software to analyse the sentiments expressed in tweets to predict real-world outcomes such as box-office revenues for films or election results11. Although the accuracy of such predictions is still a matter of debate12, Twitter began in August to post a daily political index for the US presidential election based on just such methods (election.twitter.com). At Indiana University in Bloomington, meanwhile, Johan Bollen and his colleagues have used similar software to search for correlations between public mood, as expressed on Twitter, and stock-market fluctuations13. Their results have been powerful enough for Derwent Capital, a London-based investment firm, to license Bollen's techniques.

Message received

When such Twitter-based polls began to appear around two years ago, critics wondered whether the service's relative popularity among specific demographic groups, such as young people, would skew the results. A similar debate revolves around all of the new data sets. Facebook, for example, now has close to a billion users, yet young people are still overrepresented among them. There are also differences between online and real-world communication, and it is not clear whether results from one sphere will apply in the other. “We often extrapolate from how one technology is used by one group to how humans in general interact,” notes Samuel Arbesman, a network scientist at Harvard University. But that, he says, “might not necessarily be reasonable”.

Proponents counter that these are not new problems. Almost all survey data contain some amount of demographic skew, and social scientists have developed a variety of weighting methods to redress the balance. If the bias in a particular data set, such as an excess of one group or another on Facebook, is understood, the results can be adjusted to account for it.

““We didn't imagine in the 1970s that we could work with data on this scale.””

Services such as Facebook and Twitter are also becoming increasingly widely used, reducing the bias. And even if the bias remains, it is arguably less severe than that in other data sets such as those for psychology and human behaviour, where most work is done on university students from Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic societies (often denoted WEIRD).

Granovetter has a more philosophical reservation about the influx of big data into his field. He says he is “very interested” in the new methods, but fears that the focus on data detracts from the need to get a better theoretical grasp on social systems. “Even the very best of these computational articles are largely focused on existing theories,” he says. “That's valuable, but it is only one piece of what needs to be done.” Granovetter's weak-ties paper6, for example, remains highly cited almost 40 years later. Yet it was “more or less data-free”, he says. “It didn't result from data analyses, it resulted from thinking about other studies. That is a separate activity and we need to have people doing that.”

The new breed of social scientists are also wrestling with the issue of data access. “Many of the emerging 'big data' come from private sources that are inaccessible to other researchers,” Bernardo Huberman, a computer scientist at HP Labs in Palo Alto, wrote in February14. “The data source may be hidden, compounding problems of verification, as well as concerns about the generality of the results.”

A prime example is Facebook's in-house research team, which routinely uses data about the interactions among the network's 900 million users for its own studies, including a re-evaluation of the famous claim that any two people on Earth are just six introductions apart. (It puts the figure at five15.) But the group publishes only the conclusions, not the raw data, in part because of privacy concerns. In July, Facebook announced that it was exploring a plan that would give external researchers the chance to check the in-house group's published conclusions against aggregated, anonymized data — but only for a limited time, and only if the outsiders first travelled to Facebook headquarters16.

In the short term, computational social scientists are more concerned about cultural problems in their discipline. Several institutions, including Harvard, have created programmes in the new field, but the power of academic boundaries is such that there is often little traffic between different departments. At Columbia University in New York, social scientist and network theorist Duncan Watts recalls a recent scheduling error that forced him to combine meetings with graduate students in computer science and sociology. “It was abundantly clear that these two groups could really use each other: the computer-science students had much better methodological chops than their sociology counterparts, but the sociologists had much more interesting questions,” he says. “And yet they'd never heard of each other, nor had it ever occurred to any of them to walk over to the other's department.”

Many researchers remain unaware of the power of the new data, agrees Harvard social scientist David Lazar, lead author on the 2009 manifesto. Little data-driven work is making it into top social-science journals. And computer-science conferences that focus on social issues, such as the Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, held in Dublin in June, attract few social scientists.

Nonetheless, says Lazar, with landmark papers appearing in leading journals and data sets on societal-wide behaviours available for the first time, those barriers are steadily breaking down. “The changes are more in front of us than behind us,” he says.

Certainly that is Kleinberg's perception. “I think of myself as a computer scientist who is interested in social questions,” he says. “But these boundaries are becoming hard to discern.”

- Nature

- 488,

- 448–450

- ()

- doi:10.1038/488448a

viernes, 3 de agosto de 2012

Redes sociales: Facejobs y Twittjobs

Vida digital / Ante la posibilidad de llegar a más contactos

Más gente pide empleo vía redes sociales

Cada vez se ven más búsquedas publicadas en Twitter y en Facebook; también las empresas las utilizan para detectar talentos

Nunca se imaginó que lo conseguiría a través de Facebook . Sí por alguna recomendación, un amigo, un contacto. Hacía dos años que Diego Marcatelli, de 31, no tenía un trabajo fijo. Mientras tanto, se las arreglaba con uno temporario de eventos infantiles. Había tirado currículums en distintos negocios de San Nicolás sin respuesta. "Te vamos a llamar, nos vamos a comunicar con vos", le decían, pero nunca le llegó nada.

A Germán De Bonis lo conocía de unas charlas que éste había dado en una ONG. Y, como le gustó lo que habló, lo agregó en Facebook . Y un día esa amistad virtual se activó: navegando por la red social se enteró de la existencia de un grupo creado justamente por Germán, CunsuEmpleos, donde subían las ofertas y demandas laborales de la zona. Con un sólo clic, Diego ya era miembro del grupo. Lo chequeaba a diario. Se necesita un mozo, un supervisor, un repositor. Y al mes, encontró algo que le interesaba: asesores de venta. Voy a probar se dijo. Contactó a Germán que le pasó la página a donde enviar ese currículum, y a pocos días ya tenía una entrevista. De 90 postulantes quedaron tres: Diego fue uno de ellos. Y hace una semana que ya está trabajando.

Es cierto que las búsquedas de empleo a través de las redes sociales no siempre tienen este final deseado. A veces son gritos que parecen quedar flotando en un muro de Facebook sin respuesta alguna, o un pedido que se multiplica a fuerza de retweets pero que nunca vuelve con una solución a mano. Pero, sin duda, es algo que se ve cada vez más en redes sociales comoTwitter y Facebook, redes que justamente no tienen fines profesionales como sí LinkedIn o los portales de empleos.

Alejandro Melamed, doctor en ciencias económicas y autor de Empresas + Humanas, opina que este uso de las redes sociales es un mecanismo que cada vez se está imponiendo más. "Sirven como caminos alternativos y cada vez más compañías también lo están utilizando. Brindan más practicidad, acortan caminos y permiten conectarse con más gente", dice.

Este combo de celeridad, cercanía y conexión inmediata con cualquier lugar del mundo tiene, sin embargo, otras cuestiones a las que atender. "Lo que hay que tener en cuenta a su vez -dice Melamed- es que todo lo que publicamos en la Web es público. Y probablemente esa persona que nos entreviste ya conozca todo sobre nosotros. Pero también es importante saber que, si no figuramos, no existimos."

Para Dolores Rueda, fundadora y directora de la consultora en empleos y gestión de recursos humanos Dolores Rueda Selectores, donde reciben por día unas cien postulaciones, la principal función de las redes sociales en materia laboral se resume en la siguiente ecuación: llegar a más gente en menor tiempo. Algo que no sólo es ventajoso para las empresas a la hora del reclutamiento, sino también para el candidato.

"Nosotros posteamos todas las búsquedas del mercado, no sólo las de la empresa. Y todos los que me siguen en Twitter pueden tener a mano esas búsquedas. Además, hace 20 años tenías que pelear más para llegar al dueño de una consultora. Hoy estás a un tweet", dice Rueda, quien se encarga de manejar personalmente el Twitter de la consultora. Y pone otro ejemplo: antes, quien llamaba a las oficinas después de horario seguramente era atendido por un contestador automático. Hoy, si dan con ella online, la pueden consultar directamente a través de las redes sociales más allá del horario de oficina.

RIESGO DE ENGAÑOS

Ante la consulta en el Facebook de LA NACION respecto de si los lectores habían buscado empleo vía redes sociales, Cecilia Ferro trajo a colación algo que se repetía en distintos comentarios: la informalidad de estas dos redes sociales. "En una primera instancia -escribió-, me parecen vías muy informales para buscar trabajo. Como parte de la familia de los medios, es innegable que las redes sociales repercuten lo que pasa afuera, del otro lado de la pantalla. Pero también es claro que por su gratuidad e instantaneidad dan más lugar al engaño."

En ese sentido, Dolores Rueda destaca a LinkedIn como la red ideal para las búsquedas laborales. "Lo mejor es la posibilidad de búsqueda de perfiles y el contacto con ese perfil que estás buscando. Es una herramienta de trabajo online, dinámica que tiende a reemplazar al CV. La contra es que yo no me pongo a leer LinkedIn, si no que tenés que saber qué buscar", dice.

Matías Ghidini, gerente general de la consultora en recursos humanos Ghidini Rodil, señala que de marzo a hoy la demanda laboral ha sido decreciente, algo que no quita que más gente se esté volcando a las búsquedas a través de las redes sociales. El también pone el acento en diferenciar lo que es una red profesional, como LinkedIn, de una red social. "Con Facebook o cualquier red social el problema no es la herramienta sino cómo se la utiliza. La herramienta per se no es mala. Pero en el fondo Facebook te sirve como comunicación, pero no como reclutamiento."

Aunque Facebook tiene sus excepciones, como la mencionada CunsuEmpleos o como la herramienta que ofrece el sitio de empleos Zona Jobs en esa red social, Zona Jobs Professional, que permite tener un perfil profesional distinto del personal. Tal vez una buena solución para aquellos que no quieren mezclar las cosas a la hora de la búsqueda laboral en Internet.

EN TWITTER

- @FreakyXime

XIMENA SAMBAN

"Busco trabajo en la zona de Parana o Santa Fe. Gracias"

- @MattiPerez

MATÍAS PÉREZ

" @fantinofantino Ale, soy DT de Fútbol Femenino. Busco trabajo. Te molesto con un RT. Gracias"

- @alusalerno

ALDI SALERNO

"Busco trabajo! D:"

- @PituRomero

NATA ROMERO

"Busco empleo en Bs As!! preferiblemente en el campo de ARQ!! .... favor RT"

- @mividaella

AYELÉN

"Busco trabajo, si es posible en el área de producción de tv/ cine/afines. Si alguien sabe algo lo agradecería mucho"

miércoles, 1 de agosto de 2012

Reproducir boca a boca

El boca a boca: tu mejor publicidad

Las redes sociales hicieron un boom de este tipo de comunicación que pone la opinión de usuarios, amigos y contactos por encima de todo; conocé sus beneficios

Si estás empezando tu negocio, sabemos que es probable que no tengas presupuesto para difundir tu producto. Sin embargo, hay algo que sí podés hacer y que siglos de historia confirman como el más exitoso recurso: la publicidad boca a boca . ¿Te suena a trabajo de hormiga? No, nada que ver. En épocas de redes sociales y gurúes del marketing, todo se amplifica. Un reconocido consultor alemán, Martín Oetting, explica que la premisa básica de esta estrategia indica que les damos más credibilidad a comentarios de familiares, amigos y conocidos que a los mensajes publicitarios.

Por eso, para generar una campaña de "boca a boca" , lo importante es que identifiques a un grupo de personas representativo de tu público objetivo (que imaginás como tus clientes ideales) para ponerlas en contacto con tu producto o servicio. No es sólo que se enteren de lo que estás haciendo, sino generarles una experiencia de consumo lo más satisfactoria posible.En otras palabras: no sólo se los contás, sino que hacés que lo vivan.

¿Cómo lograrlo? Bueno, podés empezar con el envío de muestras o promoviendo algún evento en el que se produzca el acercamiento. Con eso te garantizás cierta publicidad positiva en algunos ámbitos, pero la idea es dar un paso más y lograr mayor alcance. Y ahí es donde entran a jugar las redes sociales. Así, a la hora de cerrar tu plan de difusión, los integrantes del "panel" que elegiste para el testeo deberían volcar sus opiniones en Facebook, Twitter o cualquier otra red social en boga. De esta forma, lográs lo que los especialistas en marketing llaman "viralizar" el mensaje.

Lo bueno de estas campañas (a las que suelen recurrir las empresas de consumo masivo) es que se adaptan a todos los presupuestos y te permiten focalizar los recursos económicos que tengas para dirigir la publicidad a quienes creés que pueden ser tus clientes. Si necesitás un poco más de orientación, podés visitar el sitio de la Cámara de Anunciantes .

Además, acá te dejamos un video para que vean la importancia del "boca a boca" o "Word of mouth" (WOM), como lo llaman en la tierra del tío Sam.

WOM: el valor de la publicidad boca a boca

¿Qué piensan de la publicidad "boca a boca"? ¿Qué peso tiene? ¿Qué influye más en su decisión de compra una publicidad televisiva o el consejo de una amiga? Y si tenés tu propia empresa, ¿usas internet y las redes sociales para promocionar lo que hacés?

Informe: Cecilia Boufflet y Virginia Porcella

lunes, 18 de junio de 2012

ARS: Invariancia en la interacción

Social Networks Over Time and the Invariants of Interaction

- By Samuel Arbesman

- June 1, 2012 |

- 12:13 pm |

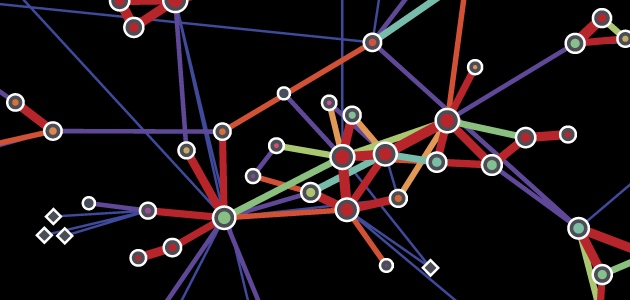

We are all embedded within social networks. Who we interact with can affect the choices we each make as individuals. Therefore, if we can quantitatively study social networks, we can better understand human behavior.

This insight is far from new. People have been thinking about the mathematics of social networks for years, with many intriguing insights. I recently added to this literature as joint first author, along with A. James O’Malley , on a paper published over atPLoS ONE entitled Egocentric Social Network Structure, Health, and Pro-Social Behaviors in a National Panel Study of Americans .

We collaborated with the folks at Gallup to do a longitudinal survey of people’s social networks. Of course, we’re unable to determine the complete social structure of the United States (we’ll leave that to the Data team at Facebook), so we sampled a representative population of several thousand Americans and examined their close social contacts, how each person’s contact are connected to each other, and how this changes over time. [As an aside, if you are in the market for a good social network survey tool, talk to Gallup. I think we developed a pretty awesome tool.]

Recapitulating other classic research, we found that the average number of close social contacts (like a spouse or good friend, not just your acquaintances) is only about four. But we also were able to determine how these network connections (number/degree and closeness), as well as how friends are connected to each other (transitivity), changed over time. Some of the findings about social ties over time are summarized in this chart below:

We found some interesting results. The most intriguing is an invariant in our interactions: just as Dunbar’s Number limits our social connections, there is also a clear relationship between the closeness to one’s social contacts and the total number of contacts you have.

Just as there are certain cognitive limits to the number of individuals one can have as part of one’s social network, it also appears that there are cognitive and temporal considerations for how humans manage their interactions. In particular, we find that the reported average closeness to all friends decreases as the number of one’s friends increases, suggesting an invariant total expenditure on social interaction [emphasis added]. An increase of one in the number of close social contacts was associated with a decrease of 0.03 in the average closeness of each individual contact on a scale where 0 = do not know and 1 = extremely close. An increase of two close contacts was associated with a decrease in closeness of nearly 0.06 (a substantial reduction on this scale). Because, in prior research, ties are typically modeled as either present or absent, with no strength information, these findings are some of the first of their kind.

In addition, we surveyed the respondents about their health and various pro-social behaviors (such as giving blood). And we found that these are related to our social networks. Specifically, “having more friends is associated with an improvement in health, while being healthy and prosocial is associated with closer relationships. Specifically, a unit increase in health is associated with an expected 0.45 percentage-point increase in average closeness, while adding a prosocial activity is associated with a 0.46 percentage-point increase in the closeness of one’s relationships.”

We are embedded within networks, which are related to how we help others, and even to our health. But these network connections are not unbounded: we have a finite social attention span. As we gain more friends, we become less close to all of them. So this embeddedness in networks is a precious thing. Understand the implications of social connections and use them wisely.

ARS: Las pequeñas cajas de Wellman

Cuando se piensa en las ciudades digitales es en términos de grupos de comunidad. Sin embargo, el mundo está compuesto de redes sociales y no de grupos. Este artículo explora cómo las comunidades han cambiado de "pequeñas cajas" de alta densidad (alta densidad vinculando a personas puerta a puerta) hacia redes "glocalizadas" (ralamente tejidas pero con grupos, vinculando los hogares tanto a nivel local y global) a "redes individualistas" (de baja densidad pero que une individuos sin importar el espacio). La transformación afecta a las consideraciones de diseño para los sistemas informáticos que apoyen las ciudades digitales.

sábado, 2 de junio de 2012

ARS: Redes de amistad y estatus social

En los estudios empíricos de las redes de amistad los participantes son preguntados, en entrevistas o cuestionarios, para que identifiquen a todos o algunos de sus amigos más cercanos, dando lugar a una red dirigida en la que las amistades pueden, ya menudo lo hacen, correr en una sola dirección entre un par de individuos. Aquí se analiza una gran colección de este tipo de redes que representan a las amistades entre los estudiantes de escuelas secundarias y primarias de EE.UU. para demostrar que el patrón de amistades no correspondido no es aleatoria. En todas las redes, sin excepción, nos encontramos con que existe una clasificación de participantes, de abajo hacia arriba, de tal manera que casi todas las amistades no correspondidas consisten en una amistad persona de menor rango reclamando por uno de mayor ranking. Se presenta un método de máxima verosimilitud para deducir dichas clasificaciones a partir de datos observados de la red y la conjetura de que la clasificación refleje producido una medida de estatus social. Tomamos nota, en particular, que la amistad recíproca y no recíproca obedecen a la estadística diferentes, lo que sugiere diferentes procesos de formación, y que las clasificaciones se correlacionan con otras características de los participantes que se asocian tradicionalmente con el estado, como la edad y la popularidad general, medida por el número total de amigos.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)